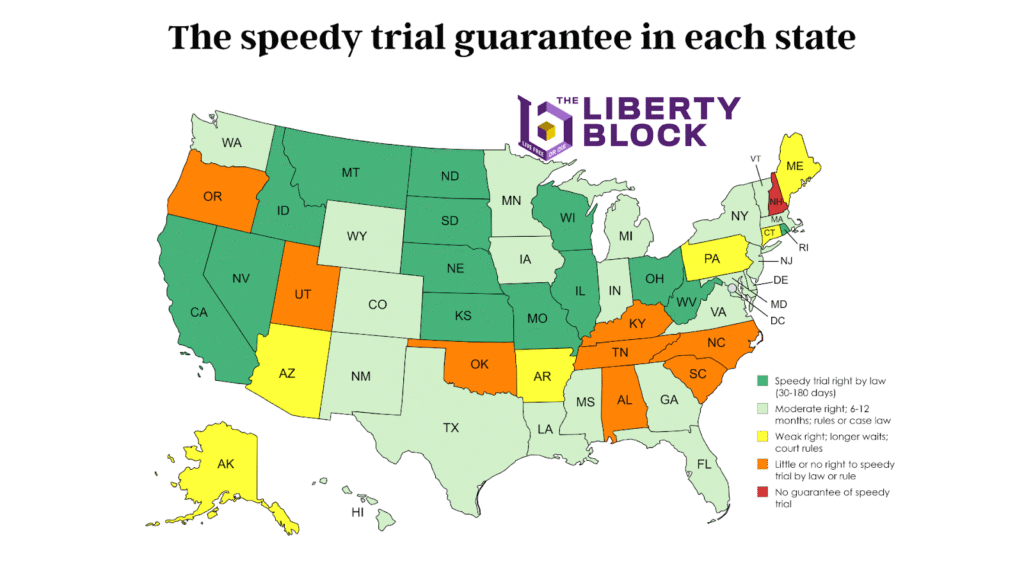

It depends where you live.

If you are suspected of a crime, you might wish to have a trial as soon as possible so that you can clear your name, get back to work, get out of jail or off bail conditions, and stop the anxiety that comes with criminal charges. The founders believed that the right to a quick trial was so fundamental that they explicitly guaranteed it in the 6th Amendment. Unfortunately, they didn’t establish a specific time limit. In a rare example of judicial restraint, the Supreme Court has also refused to define what a speedy trial means. Each state has distinct approaches to the speedy trial right. Most states address general or specific time limits via their constitutions, laws, case precedents, and court rules. Forty states and D.C. have laws establishing the right for defendants.

The American Bar Association recommends that “The presumptive limit for persons who are on pretrial release should be 180 days from the date of the defendant’s first appearance in court after either the filing of any charging instrument or the issuance of a citation or summons. Shorter presumptive speedy trial time limits should be set for persons charged with minor offenses.”

The federal government considers 70 days to be the maximum allowable delay from arraignment to trial for federal prosecutions.

California seems to have the best statutory protection for defendants. State law guarantees a trial or dismissal within 45 days of arraignment and within 30 days if the defendant is in jail. States like Wisconsin, Missouri, and Rhode Island have laws stating clear timelines for a speedy trial, ranging from 60 to 180 days. Others in this tier are ID, NV, MT, ND, SD, NE, KS, IL, OH, and WV. States like Virginia have state laws requiring a trial to be held for defendants within nine months, and five months if incarcerated. States in this group are light green in the map and have moderate lengths by law or short lengths by state court rules/criminal procedure. NY, VT, MA, NJ, DE, MD, GA, FL, MS, MI, IN, LA, TX, NM, CO, WY, WA, and HI are in this class. The yellow states don’t have any laws explicitly establishing a length of time and have only weak rules or case law that still allow defendants to wait a relatively long time for trial. These include ME, PA, AR, AZ, and AK. Alaska’s rule is 120 days, while Arkansas and Pennsylvania allow a full year before trial. The orange category is reserved for states with sparse protections for this Sixth Amendment right; only weak rules or case law relating to how long defendants could be forced to wait before trial. Oregon, Utah, and Oklahoma are joined by the southern states of KY, TN, NC, SC, and AL in this group. These states may have supreme court decisions that ruled on specific cases, but are likely not binding for future courts. New Hampshire appears to stand alone as the worst state for defendants wishing for a quick trial after being charged. While its superior court has a “rule” that encourages courts to limit the wait to six months, the district courts have no rule whatsoever and can keep misdemeanor defendants waiting forever. These people aren’t facing felony charges but are still at risk of going to jail or being placed on the sex offender registry for life. The state entirely lacks a law that addresses the issue, except for a peculiar law granting the affirmative right to accusers in certain cases. The state supreme court has only addressed the issue a few times and has ruled that delays of many years are generally acceptable.

In speaking with numerous New Hampshire legislators, none were interested in supporting a bill to enshrine the right to a speedy trial in state law.

In researching all 50 states, I found some other quirks. Some states give the prosecution the same right to demand a speedy trial as the defendant. Some states make the defendant file the motion within a few days of the arrest and consider the right waived if they fail to do so.

I wrote a short book called Delayed & Denied, which expands on the right to a speedy trial.

A caveat: It seems from my research that these laws and rules are generally enforced rather weakly. They all have language that allows for the judges to extend the trial beyond the prescribed time limits by using their “discretion” or for “good cause.” Therefore, even a state that has a guaranteed speedy trial right within 45 days of arrest on paper might realistically make defendants wait years for a trial.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Liberty Block or any of its members. We welcome all forms of serious feedback and debate.