While blockbuster cases like Garland v. Cargill (bump stock ban), U.S. v. Rahimi (restraining orders & gun control), FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (abortion pill), Murthy v. Missouri (censorship) and Trump v. U.S. (immunity) are making all the headlines, another recent decision by the Supreme Court caught my attention due to my interest in due process and government accountability.

This case concerns the availability of federal lawsuits against police officers for false arrests. This is referred to as a “Fourth Amendment malicious-prosecution claim under 42 U. S. C. §1983.” In the decision, SCOTUS explains that “ . . . a pretrial detention counts as an unreasonable seizure, and so is illegal, unless it is based on probable cause.”

In order to win a malicious-prosecution lawsuit against a cop, the plaintiff must prove

1) the appropriate intent by the cop

2) favorable termination of the case (didn’t result in a conviction), and

3) initiation of legal process.

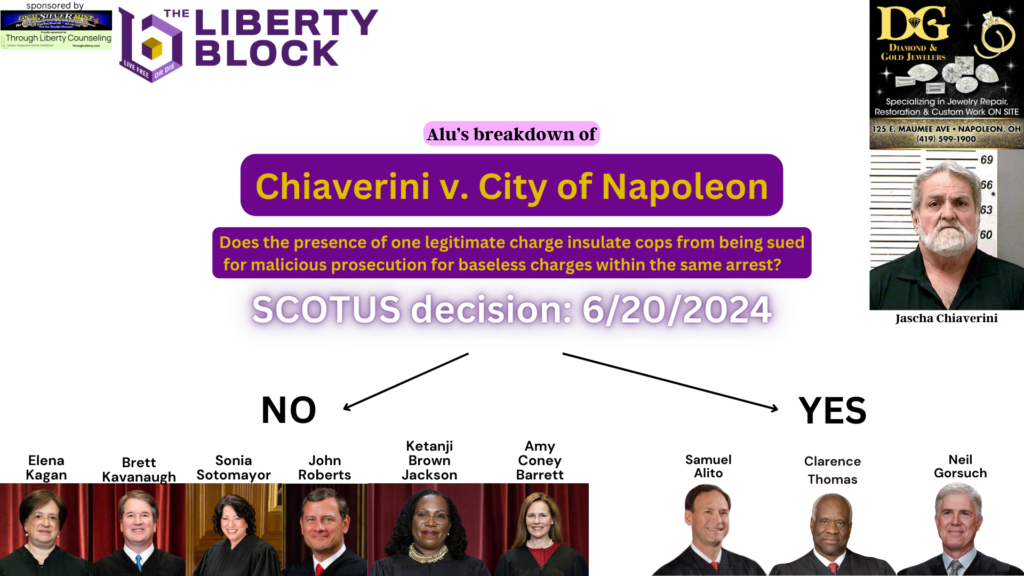

The question addressed by SCOTUS in this case: Can a person sue cops for detaining someone in jail for a charge that didn’t have probable cause if other charges within the same arrest did have probable cause; does the presence of a legitimate charge (one supported by probable cause) categorically bar a lawsuit against a cop for malicious-prosecution?

The facts of the case, according to Oyez: Jascha Chiaverini, manager of the Diamond and Gold Outlet in Napoleon, Ohio, bought a men’s ring and diamond earring from Brent Burns for $45. He recorded the transaction, including copying Burns’ ID and photographing the items. Subsequently, David and Christina Hill contacted Chiaverini, claiming the jewelry was stolen from them. Chiaverini advised them to report this to the police but denied buying their described items. After multiple calls, Chiaverini ended the conversation. Both parties contacted the police. Chiaverini expressed his suspicion about holding stolen property and requested police, not the Hills, to visit. When the police arrived, Chiaverini cooperated, providing information and photographs of the jewelry. The situation escalated when Chiaverini received a conflicting “hold letter” from the police, instructing him to keep the items as evidence but also to release them to the Hills. Chiaverini refused to release the items, citing legal concerns and advice from his counsel. His confrontation with Police Chief Weitzel revealed Chiaverini’s lack of a precious-metal-dealer license, prompting a new investigation angle. Officer Steward updated the police report to include Chiaverini’s suspicion about the stolen nature of the items, which Chiaverini disputed. Based on these developments, warrants were issued for Chiaverini’s arrest and the search of his store, leading to his temporary detention. Although a court later dismissed the criminal case against Chiaverini, he filed a complaint against the officers and the city, alleging various legal violations. The district court granted summary judgment to the officers, citing probable cause for Chiaverini’s arrest and dismissing his claims. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed.

There were conflicting opinions on this issue from various federal courts of appeal, which is likely one of the major reasons SCOTUS took up the case.

SCOTUS held by a 6-3 majority that the presence of probable cause for one charge in a criminal proceeding does not categorically insulate police from a 4th Amendment malicious-prosecution claim relating to another, baseless charge.

Ultimately, the question before the court revolved around causation: did the arrest warrant based on a cop’s lie about the felony cause the judge to sign the warrant? In this case, Chiaverini was held in jail for four days based on a warrant in which the judge literally said he approved the warrant because it involved a felony. If not for the felony predicated on the cop’s lie, the judge would not have approved the arrest warrant and the cops would have issued a summons to Chiaverini for the two nonviolent misdemeanors.

Throughout the oral arguments, the lawyers often reference Thompson v. Clark (2022), in which SCOTUS held that to demonstrate favorable termination of criminal prosecution for purposes of a malicious prosecution claim, a plaintiff need not show that the criminal prosecution ended with some affirmative indication of innocence but need only show that his prosecution ended without a conviction.

Ultimately, this decision by the Supreme Court technically makes it easier to overcome the first of the numerous major hurdles to suing police for wrongful arrests.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Liberty Block or any of its members. We welcome all forms of serious feedback and debate.