At long last, SCOTUS has published their decision in U.S. v. Rahimi. The case arose from a conviction of a Texas man named Zackey Rahimi, who was found guilty of violating a federal law. Specifically, Rahimi violated 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8), which prohibits the possession of firearms by anyone who is the subject of a domestic violence restraining order. Interestingly, the restraining orders are issued by state courts, while the law in question is federal. Additionally, each state has analogous laws making it a crime for someone to possess firearms while being the subject of a restraining order. Rahimi challenged the federal law as unconstitutional on its face due to conflicting with the Second Amendment as interpreted in NYSRPA v. Bruen (2022). In Bruen, the SCOTUS held that a restriction of any firearms right (anything that conflicts with the clear text of the 2nd Amendment) could only be constitutional if the same law or policy existed at the time the Amendment was ratified in 1791. For this case, the SCOTUS would have to determine whether restraining order gun prohibitions existed in 1791, unless they wanted to scrap the Bruen test and create another standard.

Anyone who has read Presumed Guilty and/or The Pocket Guide To Killing Gun Control surely knows how I feel about this issue. As with all restrictions on firearms, this law violates the clear text of the 2nd Amendment and it violates the natural rights to self-defense and property ownership. Perhaps more importantly, restraining orders violate the essence of due process, punishing a person without a trial and without even allowing them to defend themselves in court.

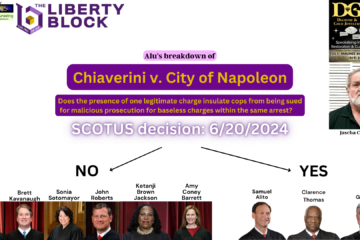

I recorded a video/podcast commenting on Friday’s court decision and I encourage you to listen to that. I have A LOT of issues with what the 8-1 majority wrote and I have a few miscellaneous thoughts about this case:

- The lengthy majority opinion does not address due process, except for acknowledging in a footnote that the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals was wrong to hold the law unconstitutional based on it being in violation of due process because Rahimi didn’t raise a due process (5th Amendment) claim in the trial court; he only challenged the law based on it violating the 2nd Amendment. Thus, the majority reasoned, the SCOTUS also cannot take due process into account in their deliberation of this case. The law may well violate due process, but they could not strike down the law based on any reasoning not brought forth by Rahimi in the trial court. I am not a lawyer, but it’s my understanding that the SCOTUS can do whatever it desires, including nullifying any law for any reason, especially if it does actually violate the Constitution. I am aware that the general rule is that appellate courts only address claims made in the original court, but I am not convinced that the SCOTUS could not have struck down § 922(g)(8) for due process reasons if they really wanted to. (Who would have stopped the SCOTUS from doing so?

In his dissent, Clarence Thomas does mention that the law clearly violates due process; it punishes people by stripping them of their most natural, constitutional, human right without adequate due process and based on the lowest (and sometimes a non-existent) standard which requires no burden of proof. Thomas said that the law “strips an individual of his ability to possess firearms and ammunition without any due process. Rather, the ban is an automatic, uncontestable consequence of certain orders. There is no hearing or opportunity to be heard on the statute’s applicability, and a court need not decide whether a person should be disarmed under §922(g)(8).”

- I regrettably neglected to mention in my video that the federal prohibition on alleged domestic abusers does not apply to a law enforcement officer’s possession of a firearm whether on or off duty. You and I can’t touch guns if anyone files a restraining order against us, but cops can keep carrying their guns no matter how many restraining orders for domestic abuse are approved by judges. Again, if the SCOTUS cared about the Constitution, this exemption would be struck down for violating the Equal Protection Clause in an instant.

- It seems like nearly every media organization (and the SCOTUS majority and nearly every other person who has commented on this case) has totally forgotten that a person is not a criminal and cannot be said to have committed a crime until he is CONVICTED of that crime. If a person accuses you of murder, you are not a murderer, and it’s defamatory to refer to you as such or to say that you killed someone. The adjective “alleged” or a similar term must be used by the media — and by judges. Yet, nearly everyone seems to have forgotten that the record shows that Rahimi had not been convicted of any crime at all when he was arrested and convicted for violating 922(g)(8). He was accused of numerous crimes, but he was not convicted of any. Thus, he must be presumed innocent. Yet, idiotic editors approve headlines like these. Rahimi could and should sue these publications for omitting the word “alleged” before the phrase “domestic abusers”. I would. He would easily win that defamation lawsuit in a sane world.

- This leads to the next point: It seems like everyone agrees that Rahimi was not a sympathetic defendant. While he was not convicted, the record indicates that police arrested him because they had probable cause to believe that he pulled out his gun and shot people on numerous occasions after his “baby-mama” filed the restraining order against him. We all knew that his character as described by the record might make it more difficult for him to win this case. The 8-1 decision is evidence that it did.

- The opinion is (likely intentionally) ambiguous about some very important facts. One might even accuse the author (John Roberts) of being evasive or manipulative. The opinion states that “The order, entered with the consent of both parties, included a finding that Rahimi had committed family violence.” This sentence is either carelessly ambiguous or willfully deceptive. Surely, the Chief Justice of the highest court in the universe would not be so careless. It could be interpreted in a number of ways: The common reader would likely understand this to mean that Rahimi agreed to the restraining order and to the plaintiff’s allegations. Or it could mean that Rahimi agreed with the court’s findings. Or it could mean that Rahimi merely agreed with the restraining order (which he believed only prevented him from contacting the woman) but did not agree and likely didn’t know about the other restrictions attached to restraining orders, such as losing his gun rights. Having experienced the exact same issue, I can empathize with Rahimi in this matter.

- The opinion is also ambiguous or deceptive when it says that “Although Rahimi had an opportunity to contest C. M.’s testimony, he did not do so.” One might read this to mean that Rahimi attended the final hearing on the restraining order and did not contest (totally agreed with) the woman’s allegations. But a substantially different reading is that he did not attend the hearing despite the court technically providing notice of the hearing and his “opportunity to be heard” via the mail. Considering that he likely could not afford a lawyer for this ostensibly civil proceeding (he was so poor that the court appointed him a public defender for his criminal charges), it is understandable that he would be anxious about attending a hearing and representing himself.

- Similarly to #5 and #6, it seems likely that Rahimi consented to the restraining order being issued due to having little desire to communicate with the woman anyway. He likely did not understand that a restraining order does far more than criminalize contact with the plaintiff; it strips you of your gun rights. Had he understood that, would he have taken his “opportunity” to fight the order much more vigorously? Perhaps so.

- The federal statute itself is ambiguous. It says that the possession of firearms is prohibited for anyone: who is subject to a court order that—

(A) was issued after a hearing of which such person received actual notice, and at which such person had an opportunity to participate;

(B) restrains such person from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner of such person or child of such intimate partner or person, or engaging in other conduct that would place an intimate partner in reasonable fear of bodily injury to the partner or child; and

(C) includes a finding that such person represents a credible threat to the physical safety of such intimate partner or child; or by its terms explicitly prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against such intimate partner or child that would reasonably be expected to cause bodily injury.

So . . . does the prohibition apply to people who have restraining orders? Or just domestic violence restraining orders? Or only domestic violence restraining orders in which the judge also made an explicit finding that the defendant presented a credible threat to the physical safety of such intimate partner or child or orders that explicitly prohibit the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against such intimate partner or child that would reasonably be expected to cause bodily injury? And what does opportunity to be heard mean? I assume it means that the person received a letter regarding the hearing, but it likely does not mean that they actually showed up to the hearing. What about ex parte orders? The federal law does not seem to prohibit firearm possession by people subject to ex parte orders, which seems surprising to me. And what does “finding” mean? By preponderance of the evidence?

The law is especially interesting because it references orders that “prohibits the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force.” Isn’t violence and threatening violence already a crime?

- The opinion begins by telling of many terrible things that Rahimi had done, such as abusing his child’s mother, shooting at numerous people, dealing drugs, and other crimes. But it doesn’t say where those allegations came from and whether they had any evidence. Were they from probable cause affidavits filed by cops? Which cops? Were they the allegations made by the woman who filed the restraining order? Were they findings made by the judge in the restraining order case? Were they findings by a prosecutor? A judge? Were they just rumors? Did Rahimi concede to these allegations? The majority — the eight most brilliant legal authorities in the world — literally tried to pass off these horrible crimes as facts; as if Rahimi had been convicted of beating this woman and shooting people and selling drugs. In fact, the word “alleged” does not appear anywhere in the huge decision until Thomas’ dissent! Could Rahimi possibly sue the eight judges for defamation (were it not for judicial immunity)?

- The majority opinion included that “Rahimi’s facial challenge to Section 922(g)(8) requires him to ‘establish that no set of circumstances exists under which the Act would be valid.’” This is an extremely difficult standard to achieve. “That means that to prevail, the Government need only demonstrate that Section 922(g)(8) is constitutional in some of its applications.”

- The majority practically conceded that they threw away the US Constitution when analyzing this case and went straight to policy-making. Do restraining order laws make sense? Of course! Should domestic abusers have access to guns? Of course not! So, let’s uphold the federal law in question. Now . . . how can we argue that the 2nd Amendment allows the government to ban guns for people with restraining orders???

- a) To the extent that the majority attempted to justify the law via the Bruen lens of historical analogues, they presented two ancient laws: surety bonds and “going armed” laws. The judges say that “Surety laws were a form of “preventive justice,” 4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 251 (10th ed. 1787), which authorized magistrates to require individuals suspected of future misbehavior to post a bond. If an individual failed to post a bond, he would be jailed. If the individual did post a bond and then broke the peace, the bond would be forfeit. Surety laws could be invoked to prevent all forms of violence, including spousal abuse, and also targeted the misuse of firearms. These laws often offered the accused significant procedural protections.” This was a law in England before the US Constitution existed and was so anti-due-process that no modern judge outside of North Korea would consider it to be constitutional. That is not a historical analogue. If we were to endorse English laws from the 1700s as inherently acceptable, should we not now cut the heads off anyone who demeans the government?

But the whole “surety bond” system is actually quite different from the restraining order gun confiscation, if you think about it. The historical law simply required a potentially dangerous person to put up some collateral to discourage future violence. It didn’t actually take anyone’s guns or gun rights. The current law under scrutiny confiscates an innocent person’s firearms, ammunition, and other weapons by sending armed cops to seize his property by any means necessary. The person is totally prohibited from having any possession or access to any of the aforementioned items for the duration of the restraining order. That is absolutely not similar to the surety laws. If you were faced with a choice between gun confiscation/prohibition or putting up a collateral to ensure peace, is it possible that you’d choose the latter? I would. Therefore, the surety system was not nearly as severe a punishment as modern restraining orders. [as outlined by Thomas’ dissent]

The majority cites a 1795 Massachusetts surety law in which once a person filed a complaint, “The magistrate would take evidence, and—if he determined that cause existed for the charge—summon the accused, who could respond to the allegations.” So, this was not an ex parte proceeding. And 922(g)(8) also does not apply to ex parte orders. The good news is that this would indicate that one could still challenge ex parte orders and potentially bring that case all the way to the SCOTUS, which would have a harder time upholding such a law.

b) “The ‘going armed’ laws—a particular subset of the ancient common law prohibition on affrays, or fighting in public—provided a mechanism for punishing those who had menaced others with firearms.” Again, this is even less relevant than the surety bond concept. At least that concept was somewhat similar to restraining orders in one sense. This one seems to only apply to people who have “menaced others with firearms.” Absent any other descriptors, we must presume that those people were convicted of threatening others with firearms. (the opinion says of the “going armed” laws: Such conduct disrupted the “public order” and “le[d] almost necessarily to actual violence.”) That is vastly different from the current case, in which a person was merely accused of a crime of violence. Furthermore, we do have laws that punish people with prison and/or the stripping of their gun rights for threatening others with guns. It is generally criminalized as “aggravated assault” and it exists in every state. But before those punishments could be imposed, the defendant must be afforded due process, including a full and fair criminal trial. Regardless, this ancient concept is also very different and far less severe than the current law we are discussing. The going armed laws seemingly prohibited a person from (openly) carrying guns into town and threatening people with them. It seems quite clear that those subject to that policy could still keep guns in their own homes for self-protection. The modern restraining order totally strips 100% of gun rights from the suspect, including a total prohibition on owning firearms for home protection.

The SCOTUS seems to rely on precedent from 800 years ago to justify current laws: “From the earliest days of the common law, firearm regulations have included provisions barring people from misusing weapons to harm or menace others. The act of “go[ing] armed to terrify the King’s subjects” was recognized at common law as a “great offence.” Parliament began codifying prohibitions against such conduct as early as the 1200s and 1300s, most notably in the Statute of Northampton of 1328. . . . The Militia Act of 1662, for example, authorized the King’s agents to “seize all Armes in the custody or possession of any person . . . judge[d] dangerous to the Peace of the Kingdome.” Again, by the same token, we could have 75 year old kings taking any 12 year old they desire as their wife and beheading any dissenters. We are not in the 1300s. If we are to revert back to the 1770s, we should abolish the modern income tax and all federal agencies, return to a gold standard, and cut federal spending by 99.9999999%.

- Until Thomas’ dissent, nobody seemed interested in addressing the single most critical issue: what is the standard for the burden of proof? Could a person be stripped of their human rights based on a preponderance of the evidence or only beyond a reasonable doubt? What about probable cause? Or reasonable suspicion? What about ex parte proceedings? It is troubling that the eight judges in the majority totally ignored these critical questions. Thankfully, Thomas said that “Civil proceedings also do not require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, and some States even set aside the rules of evidence, allowing parties to rely on hearsay.” Oh, how right you are, Mr. Thomas! Initial restraining orders seem to be approved by judges without any scrutiny whatsoever; I have yet to hear of a single application for one being rejected! The statutes that create restraining orders do say that the judges should only approve the requests if there is evidence of abuse, but in practice, judges rubber-stamp almost all of them as a matter of routine.

- The SCOTUS cites itself as canon justifying their decision: “Like most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. District of Columbia v. Heller (2008).” Circular logic and appealing to oneself as authority in order to prove something is ridiculous. But the SCOTUS does it all the time and calls it “precedent” or stare decisis in Latin. The majority does cite others, though: “From Blackstone through the 19th-century cases, commentators and courts routinely explained that the right was not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose.” Who made Blackstone God? Why should I care what commentators and other courts think? They can’t change the 2nd Amendment.

- The majority gets the 2nd Amendment backwards. 2A restricts the government from imposing any restrictions on firearms rights. It doesn’t grant some limited rights to individuals. The restriction is against the government, not the people. Yet, the majority says “the reach of the Second Amendment is not limited only to those arms that were in existence at the founding. Rather, it “extends, prima facie, to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not [yet] in existence.” By that same logic, the Second Amendment permits more than just those regulations identical to ones that could be found in 1791. By this logic, since the 2nd Amendment prohibits infringements on modern guns like it does historical guns, the government can make modern gun control laws even though the laws didn’t exist in the 1790s. What about the whole “historical tradition” from Bruen???

- Could the more general laws allowing for restraining orders to be filed by strangers (as opposed to only spouses or those who cohabitate) for alleged “stalking” or “harassment” still be challenged as unconstitutional due to the 2nd or 5th Amendments?

- Does this ruling empower police to confiscate guns from people with restraining orders or does it only obligate the gun owners themselves to not possess firearms? Would cops need a warrant to search and/or seize firearms? These questions remain unanswered.

- From the reading I have done so far on this issue, it seems like the only one who understands basic concepts such as “presumption of innocence” and “burden of proof” is Eugene Volokh, a law professor and columnist for Reason Magazine. His article does a good job analyzing the Rahimi decision.

- Like all laws restricting firearms possession, this federal law clearly violates the 2nd Amendment. Yes, even if the founders were here today, they would reject this law, because they were not joking when they wrote “shall not be infringed.” Thus, laws like 922(g)(8) could only be constitutional if the Constitution were amended such that the 2nd Amendment was altered or erased. And since statists often remind us that a bajillion percent of Americans support red flag laws and other “common sense” (there’s that phrase again!) gun control, shouldn’t it be super easy to pass and ratify such an amendment to the US Constitution? It could pass Congress with two-thirds in a day. And three-quarters of the state legislatures could ratify the amendment within a few days or weeks if they really wanted to. Why not amend the Constitution? It’s already been done 27 times!

- Two of the Democrats on the Court, Sotomayor and Kagan wrote separately to make it clear that they disagree with the Bruen decision and support super-strict gun control. That concurrence includes statements such as “guns in the 18th century took a long time to load, typically fired only one shot, and often misfired” and “Rather than asking whether a present-day gun regulation has a precise historical analogue, courts applying Bruen should “conside[r] whether the challenged regulation is consistent with the principles that underpin our regulatory tradition.” Being that the “principle in both historical and modern laws is to “ensure public safety,” no laws could ever violate the 2nd Amendment, according to this test. They literally reject the 2nd Amendment as a protection of gun rights: “In my view, the Second Amendment allows legislators to take account of the serious problems posed by gun violence . . . not merely by asking what their predecessors at the time of the founding or Reconstruction thought, but by listening to their constituents and crafting new and appropriately tailored solutions.” They actually called for “means-end scrutiny” in the concurrence. Sotomayor and Kagan also falsely treat Rahimi as a convicted criminal and not a suspected criminal, which is a major issue. Throughout the concurrence, they refer to him as a “domestic abuser” and do not use the adjective “alleged.”

- Thomas brilliantly points out that “mixing and matching historical laws—relying on one law’s burden and another law’s justification—defeats the purpose of a historical inquiry altogether. Given that imprisonment (which involved disarmament) existed at the founding, the Government can always satisfy this newly minted comparable-burden requirement.”

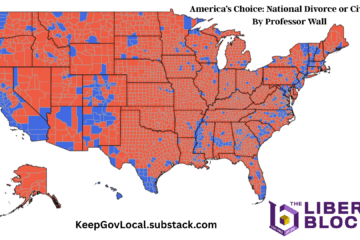

- Being that the highest court in the union has endorsed restraining order gun control and red flag gun gun prohibitions, there is even more reason for citizens of free states to consider secession from the union as a viable option.

- I address the aforementioned issues in great depth in Presumed Guilty and The Pocket Guide To Killing Gun Control. I’d appreciate it if you’d consider checking them out!

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Liberty Block or any of its members. We welcome all forms of serious feedback and debate.